“No family or culture leaves its young unmarked; by a thousand cuts, we shape the bodies and minds of our progeny. All human communities have a sense of what an ideal man or woman looks like, and all children —even those with the happiest childhoods — emerge locally marked or, to say it more positively, inscribed with a serviceable identity to be carried out of childhood into the given world, happily so if the child is lucky and loved, and necessarily so, as well, for — as much as we might value the spiritual practice of thinning out the self, of noticing its contingency and transience, of muting its fear and greed — there can be no forgetting the self until there is a self.”

Lewis Hyde, A Primer for Forgetting

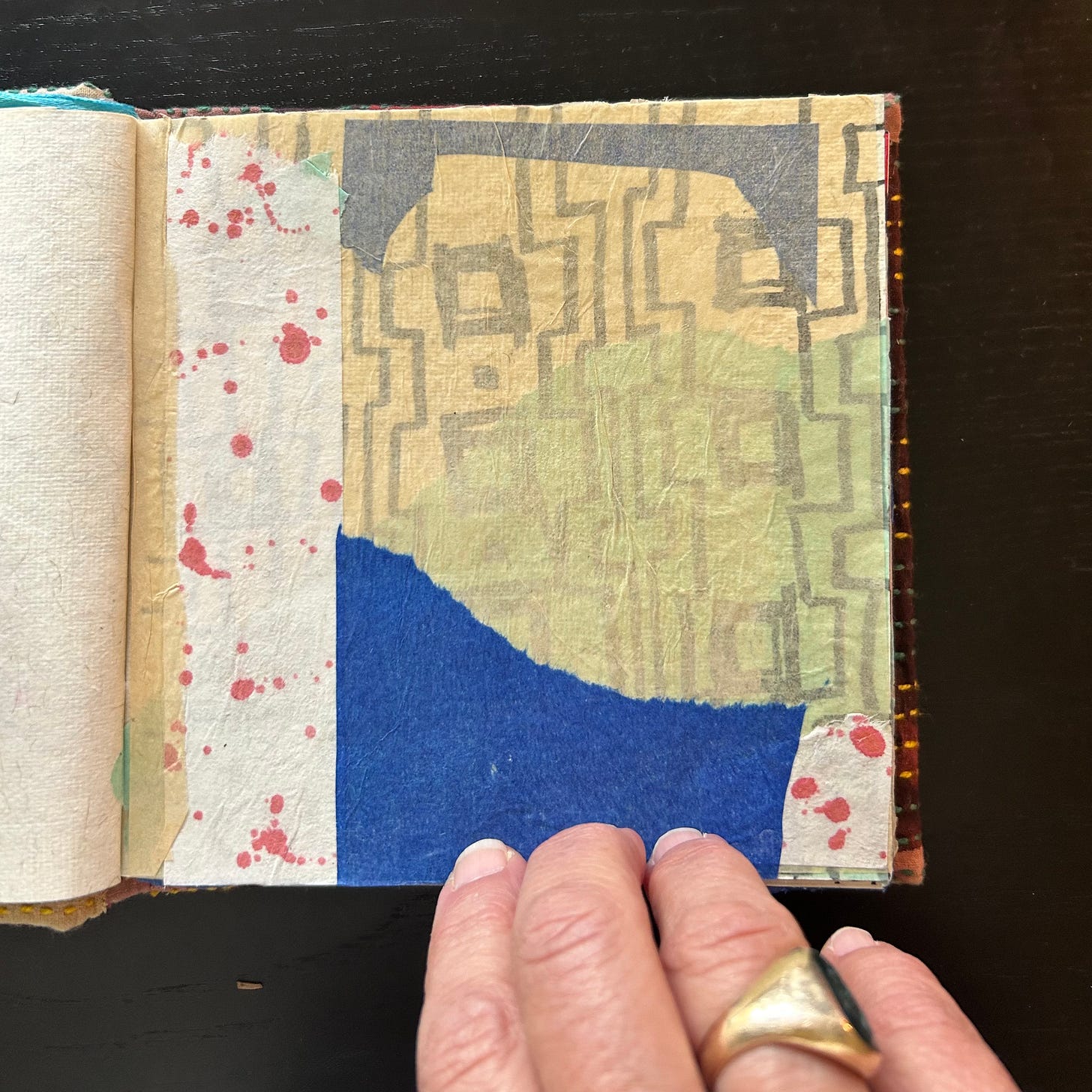

We have been discussing passages from A Primer for Forgetting in our workshops. The book is filled with rich ideas about how memory (and forgetting) operates through cultural, mythological, national, and personal narratives. In the first section of the book, Lewis Hyde presents the rites of childhood (the notion he calls tribal scars) as formative cultural or familial pillars so engrained in one’s sense of self that they are difficult to identify. It can feel painful to pull away that which has been imprinted on us and examine ourselves in a new light. The exercise allows us to better understand our cultural inheritance. It provides us with new respect for what has shaped us, and in other cases, an opportunity to set aside those impediments that have caused us harm.

Our different writing groups identified the tribal scarring in their own biographies. As we shared stories, we readily identified patterns of food insecurity, generational cycles of addiction and incarceration, incidents of physical abuse, and stints in foster care. In most cases, our writers were put into adult situations long before they reached puberty. This week we have assembled passages of clear-eyed writing.

Theron Hall’s Didn’t know I was a Victim was first published in our anthology, Prisons Have A Long Memory: “I was stabbed in a gang fight at sixteen. The police arrived on the scene and a witness told them what they saw. The officers approached me and directed me to turn around and lift up my shirt. As I complied, they saw blood running down my back, confirming the witness’s statement. Asked what happened, I refused to cooperate. The culture that surrounds childhood trauma normalizes violence and poverty.”

Faith of the Scar by Le’Var Howard

Give what

you earn to provide for the table,

your tribe prepares.

Old Scars by J. Hunter

Waiting to hear the steel toe

boots climb the stairs,

pushing away the fear

deep within that I feel.

Tribal Scars by Walter Thomas

Then my grandmother started going blind, and so did I. Physically I could still see the streets, the buildings, and the cars, but mentally I stopped seeing my future.

The Game by R. Miranda

My body wears the scars …

scars from a life lived “in the game.”

Pushing pills, hustling heron, slinging ‘cain …

My body is riddled with bullet holes —

American: The Scar is Hope by Le’Var Howard

American hope is the thing of

dreams. A thing of

prayers. A praise of songs, a dance

to face fears and confront

evils. A scar is a boyhood

dream for Americans.

And finally, I have been thinking about this interview with Ocean Vuong for the past two weeks. In it he describes a defining moment during his adolescence, one that so many of our writers have experienced. The difference? Vuong was not handed the gun. A scar is a boyhood dream for Americans. | TDS