EDITOR’S NOTE: THIS ESSAY ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN PRISONS HAVE A LONG MEMORY: LIFE INSIDE OREGON’S OLDEST PRISON, THE WRITING REFERENCED IN THIS PIECE CAN BE FOUND IN THE ANTHOLOGY.

Sunday morning, crows in the park woke me. They were distant, but noisy. I let my mind wander back to that faraway sound, and it got closer. The key turned and I remembered waking in a field, on an island. I peered out of my sleeping bag. There was dried yellow grass crushed below me, seeds stuck in my hair. Steam rose from the sleeping bag, sun drying the dew. My nose was cold, my legs a sweaty tangle in the bag. I was still far from home. I missed the familiar sound of my life, the carpet underfoot when I walked down the hall. What was more uncomfortable: being hot and bound in this sleeping bag or the homesick weight returning to my chest?

I lifted my head to see the blue-black crows. The field was dotted with brightly colored sleeping bags laid out on orange tarps — the mummified bodies inside were still. I was usually the first awake: morning, the homophone of “mourning.” The crows picked at the butter we’d left out in our makeshift kitchen. We were young girls, careless in our cleanup from the campout the night before. Fat-glazed beaks glinted in the light. They were pecking at our unintentional meal, much like the grief had punctured my sleep.

Forty years later, my girl is in the doghouse. Her first major act as a twelve-year-old involved hurting someone’s feelings. She was immediately sorry. We agreed to stow away her phone until she returned from camp. Apologies were written and we waited until heads and hearts healed.

I look over at her on the couch in our living room. She is curled around a book, a posture as natural as fetal position is to the sleeping. She looks like a teenager, and I flash on myself at her age: “She is biding her time until she is a grown-up.” Like a person waiting for a bus, she is reading until adulthood arrives. I remember looking up from my own book to scan an unchanged world, and then returning to the pages, where things were happening. Nancy Drew drove her roadster through River Heights to solve mysteries. Nancy’s dead mother was the secret to her being a sixteen-year-old sleuth. All the best adventures happen when the adults have gone away. At the very least, this is what I read and believed. And when my daughter looks up from her book, I recognize her look of tired resignation: “I am stuck here for a while longer.”

Many of the men we meet at OSP fell when they were still embroiled in the turmoil of adolescence. They are guilty of having committed very serious offenses. At sentencing they are guaranteed to spend more time in prison than the total years they have lived in freedom. When (or if) they return to our communities, they will be held in a state of suspended animation. While teenage drama was cooking on my home front, we read Peter Pan in Ground Beneath Us to consider adolescent passages and those rites in each of the writers’ histories.

The clinical psychologist and professor Dr. Daniel Siegel draws on research in the field of interpersonal neurobiology as he makes a new picture of the adolescent mind in his book Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. He argues elegantly and humanely for a rite of passage between childhood and adulthood, rather than “getting through” adolescence. He recognizes that this is a time of intense neural remodeling as the child brain becomes the adult brain. By recognizing the processes underway, we adults, as well as adolescents, are able to celebrate the impulses involved in this transition (yes, even some of the riskier ones). He argues: “The ‘work’ of adolescence — the testing of boundaries, the passion to explore what is new and exciting — can lay the stage for the development of core character traits that will enable adolescents to go on to lead lives of adventure and purpose.” ⁴ Our brains are remodeled in adolescence so that we can guide the next generation.

Unlike my blunt theory of the missing parent as a catalyst for adventure, Dr. Siegel’s assessment is more nuanced. He starts with a model of parenting that involves important elements for secure human attachment: “The parent attends to children so that they feel seen, feel safe, soothed, and secure.” ⁵ Once parents have created a launching pad with these elements in place, the child has solid ground from which to try and fail, risk and succeed, risk and screw up as they form their wildly elastic brains into less plastic but strongly integrated adult ones. Risk-taking is a key component in successfully rewiring the brain.

Think of the effort it takes to walk for the first time, those faltering trials to make fat baby thighs hold up the body. The stumbling, and the teetering thumps of falling on a diapered bottom. Equal parts tears and laughter, a toddler finds her way to walk. Then think about the self-consciousness of a teenager. How each trial (walking across the lunchroom) is filled with perplexing social signals and unnerving interactions with members of different tribes. A certain amount of impulsive behavior needs to occur in order to make a move. In some ways, the impulse is the social equivalent of those early lurching steps. And with it comes that reward of propelling oneself — to the bottom of the staircase, or up the staircase! The teenage version of this desire to push away and try things alone is natural and terrifying for parents . . . and I think adults forget that it is equally frightening for the kids. It is a time when most kids wish to escape, to fly out of the nursery window to try out their independence. They need a catalyst — a sprite, a sprinkle of fairy dust, and a destination.

A magical telling of the hero’s journey from child to adult caregiver, Peter Pan centers around the Darling children, who are tucked into the arms of their parents, sleeping in their nursery. The Darlings have laid the groundwork for their children so that when they decide to set out on their adventures, they feel confident that the nursery window will remain open to welcome them home. They will be just as safe whether they grow and thrive or stumble and fail. However, Peter has an uneasy relationship with adults. He feels he has been failed by his mother, for when he returned from his adventure he was barred from the window and replaced by another boy. Peter’s attachment was severed. The hurt and distrust he felt in response to the failure of the adults in his life left him with the task of scooping up other “lost boys” and keeping them from harm — which means holding them in arrested development. To read Peter Pan as an adult is a different experience than reading it as a child.

Cameron Hayes identified the Lost Boys as a street gang and described childhood trauma as a leading factor in the formation of the band. A former gang member, Cameron works at OSP as a peer-to-peer counselor dedicated to helping fellow prisoners redirect their lives. He has studied adolescent psychology to better understand his younger self, and he chose a path forward so that he will be ready to assume his place when he clears the prison gates. Unlike Peter Pan, Cameron models healthy behavior, leads prosocial work, and teaches skills to encourage his peers. In “The Making and the Breaking,” he describes the challenging work of letting go of a strongly established antisocial identity in order to become the man he is meant to be.

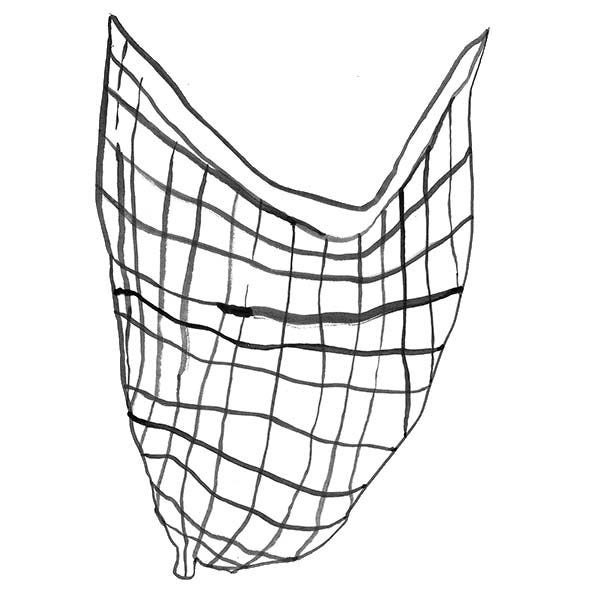

We had known Le’Var Howard for over a year when he submitted his autobiography. I read the first passage. And I put it down. I was not prepared. It took me two weeks to carefully make my way through his writing. “I was thrown into that situation with no idea — like a fish in a net, but still in water.” The violence that is enacted upon the four-year-old in the first act will be repeated. Le’Var and I exchanged the piece to sharpen it with editing. I listened to his record on iTunes, G-L the 7 Letters, and we added lyrical passages to his story: “What is life? / But to live and learn / Never forget / Where we came from.”

In the narratives, we see the writers circling intertwined trails as teenagers, young men. They are lost. A pattern emerges. We recognize that they are trying to make connections, find their tribe, but they are missing a safety net, a secure attachment. There is no landing place if they take a fall. In “I Hadn’t Carried a Gun,” Kyle Hedquist writes that by the age of thirteen, he no longer trusted adults. At that time, he was swept away to his grandparents’ farm, a place of unconditional support and love. They created a home with structure and work and animals that required his care. And yet, the powerful experience of early childhood trauma left him disconnected. Almost thirty years later, he recognizes that as a teen he was desperate to win the approval of everyone — and then, through his own actions, he loses everything. There is no question that as an adult, Kyle now wishes he could have been the parent his younger self required. With this wisdom he moves forward, working to serve others.

In his essay “The Path Through the Woods,” Philip Pullman talks about the dark place, the wild place. In a fairy tale, it contains the path, the story line, the possibility for transformation. Pullman sees the storyteller’s role as picking the path and moving through the woods. You may stop along the way to select the right details, but a good storyteller knows to keep moving. Our storytellers have inherited family histories of addiction, violence, and generational incarceration. The only rite of manhood seems to be a passage directly through the heart of the beast. This doesn’t have to be the end point of their lives, and so the men write their lives forward, composing new chapters. They write stories to make the legacy of incarceration stop with them.

Our storytellers know the dark places too well. The weight of the violence. It takes years to learn how to talk about the darkness, but they can chart the course like Joseph Campbell’s hero. Prison is mythical. Prison is real. They are now men, responsible for caring for and learning to love their younger selves. They have to create secure attachments for themselves. Words and prayers and conversations help them pick their way through the thorns, travel out of the labyrinth of punishment. Like Bear, the storyteller at Columbia River Correctional Institution, they must wrap their hands around the knife and cut their own way through the woods.

My girl returns from her Neverland adventure out of the doghouse she was in earlier in the summer. Every year, she spends a month on an island in the north. This is the place where I woke up to the crows pecking at butter. There is a wilding that happens when kids live outside — showers are infrequent and no one harps on toothbrushing. Hairbrushes disappear. Many of the counselors are kids themselves, having left their own homes just a year or two before. Campers and staff come back altered. Shoulders square differently, and they wear light around their heads. Filthy feet have been grounded by rutted trails and chores (cleaning the outhouses is called “Joy!”). Heads are filled with starlight and the dappled sun through tree leaves. Faces and arms are sunburned, covered in scabs from mosquito bites. It is heaven. And it can be hell. When you miss home, it can feel more like you were sent away than you chose to fly. We wrestle with the conundrum: Do we insist she go even though it is hard for her to be away from home?

Reading the narratives for this book, I recognize the difficulty of reconciling the writers’ past actions with who they are now. Threading a needle that provides context for one’s life choices, takes responsibility for one’s mistakes, and makes room for one to atone requires grace. In her newsletter Letters from an American, the historian Heather Cox Richardson makes this observation: “Southern novelist William Faulkner’s famous line saying ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even past,’ is usually interpreted as a reflection on how the evils of our history continue to shape the present. But Faulkner also argued, equally accurately, that the past is ‘not even past’ because what happens in the present changes the way we remember the past.” ⁶

This describes the carceral experience. A person held in a constant state of criminality — frozen as convict in the eyes of the world for ten, twenty, thirty years — can’t shed the skin of their sentence. From that moment forward they wear the label “felon.” The past action shapes their narrative, their sense of self, their place outside society. The person who fell (the shadow self) lives imprisoned by that old identity.

Flight requires practice. A pilot needs to log hours of time before finally taking off alone, and so I suppose this is why I encourage my daughter’s monthlong retreat. It is a chance for her to experience independence with training wheels. Her first week away, I received two letters on the same day: The first reported that camp was fun, and that a “smug” spider was making a web on her jeans. The second note asked if I would bring her home on visitor’s day. She was a thousand times more homesick than she’d been the previous summer. How does she resolve the tension between wanting to be at camp and wanting to be at home?

Humans are expected to hold two or more diametrically opposed emotions in our beating hearts. At times the pain is so acute that we think the muscle will finally squeeze itself into two pieces. During the remodeling of the adolescent brain, areas that are no longer used are rewired. Some of the sharp and intense emotions of this period soften with age. Our memories are linked so that days tie together into years, the way sentences become chapters. This is the kindness of aging: we are better able to hold more. Our relationships (with friends, family, enemies) have this in common: we balance on a pinhead the need for autonomy and for connection. | TDS

4. Daniel Siegel, Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain (New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2013), 312.

5. Siegel, 145.

6. Heather Cox Richardson, Letters from an American (Substack), February 27, 2022